Your doctor suggested swimming might ease your chronic back pain, but what if the evidence supporting this advice is shockingly thin? Millions receive this recommendation yearly, yet research reveals a critical gap between common medical guidance and scientific proof. Before you invest in swim gear and commit to weekly pool sessions, understanding what 3,093 research articles actually say could prevent months of wasted effort and potential pain aggravation.

Current medical guidelines consistently recommend exercise for back pain management, with swimming frequently topping the list. However, a comprehensive analysis of existing studies shows this advice rests on surprisingly shaky ground. The reality? We simply don’t have conclusive evidence that swimming specifically helps back pain—despite what your physician might tell you. This article examines exactly what science knows (and doesn’t know) about swimming for back pain relief, helping you make smarter decisions about your treatment.

Why Your Swimming Routine Might Not Relieve Back Pain (Yet)

The Cross-Sectional Evidence Trap

Over 84% of swimming-back pain studies (37 out of 44) rely on cross-sectional data—meaning researchers took a single snapshot rather than tracking changes over time. This design flaw prevents determining whether swimming causes reduced pain or whether people with less pain simply choose swimming. Imagine trying to understand if a medication works by only checking patients once—you’d never know if improvement came from the drug or other factors. That’s the fundamental problem with most swimming-back pain research today.

This methodological weakness means current recommendations lack scientific backbone. When 93% of studies treat swimming as a secondary outcome rather than their primary focus, you’re essentially following advice based on accidental observations rather than targeted research.

The Single RCT Reality Check

Only one randomized controlled trial exists in the entire swimming-back pain literature—the gold standard for medical evidence. This solitary study cannot possibly account for different swimming strokes, varying pain conditions, or diverse populations. It’s like trying to understand all car engines by examining just one model—you’ll miss critical variations that determine real-world performance.

Without multiple high-quality RCTs comparing swimming to other exercises and no-exercise groups, doctors essentially recommend swimming based on theory rather than proof. The absence of controlled evidence means your personal swimming experiment carries significant uncertainty.

Competitive Swimmer Data Misleading Your Back Pain Treatment

Why Elite Athlete Research Doesn’t Apply to You

Nearly 60% of swimming-back pain studies (23 out of 39) focus exclusively on competitive swimmers—athletes whose bodies and pain patterns differ dramatically from desk workers or older adults with degenerative conditions. These elite swimmers typically have:

– Superior core strength and flexibility

– Years of technique refinement

– Different pain tolerance levels

– Higher injury resilience from conditioning

When research examines young athletes swimming 20+ hours weekly, their findings become irrelevant to your situation as a recreational swimmer doing 30-minute sessions. Competitive swimmers’ back pain often stems from overuse rather than the sedentary lifestyle issues causing most adults’ back pain.

Missing Population Data You Need

Critical gaps exist for populations most likely seeking swimming for pain relief:

– Recreational swimmers over 40 years old

– Sedentary individuals starting exercise programs

– People with specific diagnoses like herniated discs

– Those swimming purely for therapeutic reasons

Without research on these groups, you’re essentially guessing whether swimming will help your specific back pain scenario. The science simply hasn’t investigated whether buoyancy benefits outweigh potential stroke-related strain for your particular condition.

How Stroke Choice Changes Your Back Pain Outcome

Why Breaststroke Might Worsen Your Pain

No existing study properly compares different swimming strokes for back pain outcomes—a critical oversight when each stroke impacts your spine differently. Breaststroke’s repetitive extension-flexion cycle creates significant spinal loading that could aggravate certain back conditions. Meanwhile, backstroke maintains a neutral spine position that might provide relief for disc-related pain.

Without stroke-specific evidence, you’re swimming blind regarding which technique actually benefits your pain pattern. Current research lumps all swimming together, masking potentially important differences between strokes that could make or break your pain management success.

The Dose Documentation Disaster

Researchers rarely record essential details about swimming routines:

– Which specific strokes participants performed

– Exact frequency (swims per week)

– Session duration and intensity levels

– Water temperature and depth variables

– Technique quality and coaching involvement

This lack of precision makes it impossible to determine whether 20 minutes of gentle backstroke provides different benefits than 45 minutes of intense butterfly training. You might be doing the right exercise but with the wrong parameters for your specific pain condition.

Why Doctors Recommend Swimming Without Proof

The Buoyancy Benefit Theory

Doctors recommend swimming based on three compelling theoretical advantages that lack rigorous testing:

– Water buoyancy reduces spinal loading by up to 90% compared to land

– Water resistance provides gentle strengthening without impact stress

– Horizontal position may temporarily decompress spinal discs

These potential benefits make swimming seem ideal for back pain sufferers. However, theory doesn’t equal proof—especially when research shows odds ratios varying from 0.17 (strongly protective) to 17.92 (highly damaging) across studies.

The Exercise vs. Swimming Paradox

While exercise is strongly recommended for chronic low back pain, land-based activities like walking, yoga, and core strengthening have substantially stronger research support than aquatic exercises. This creates a medical paradox: doctors prescribe swimming based on general exercise benefits despite weaker evidence specifically for swimming compared to other activities.

The recommendation persists because water exercise should work—yet we lack the data proving it actually does for most back pain sufferers.

Building Your Personal Swimming Pain Protocol

![]()

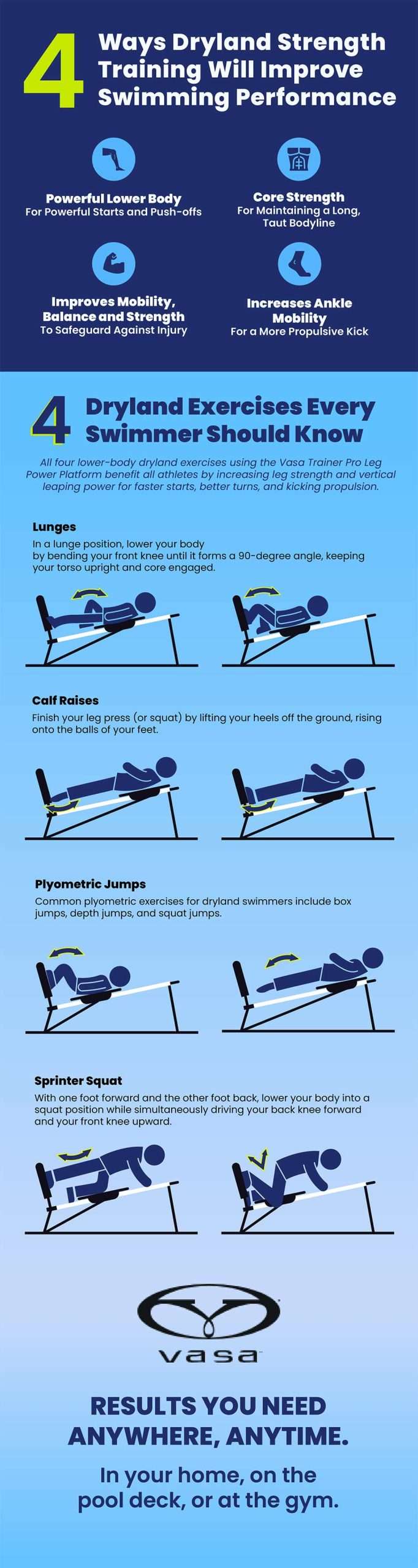

Tracking Your Pain Response Systematically

Treat your swimming routine as a personal experiment with these tracking steps:

-

Record baseline measurements before starting:

– Pain intensity (0-10 scale)

– Functional limitations (e.g., “can’t tie shoes”)

– Current pain triggers -

Implement controlled variables:

– Start with just one stroke type

– Limit sessions to 10-15 minutes initially

– Maintain consistent water temperature -

Document immediate and delayed responses:

– Pain levels during swimming

– Pain changes 2 hours post-swim

– Morning pain levels following swim days

This systematic approach reveals whether swimming actually helps your specific back pain rather than relying on general recommendations.

Stroke Selection Strategy

Choose strokes based on your pain pattern:

For disc-related pain (sciatica, herniations):

– Prioritize backstroke for neutral spine position

– Avoid breaststroke’s repetitive extension

– Try elementary backstroke for gentler movement

For facet joint or mechanical pain:

– Test freestyle with bilateral breathing

– Avoid prolonged back extension in butterfly

– Use pull buoy to reduce leg strain

For general stiffness:

– Combine multiple strokes in short intervals

– Focus on smooth, rhythmic movements

– Incorporate water walking between swimming sets

When to Stop Swimming for Back Pain Relief

Warning Signs Requiring Immediate Action

Stop swimming and consult your doctor if you experience:

– Increased pain during or after sessions (beyond normal muscle soreness)

– New neurological symptoms like numbness, tingling, or weakness

– Pain that worsens over consecutive sessions despite proper technique

– Difficulty maintaining form due to pain (indicating potential compensation)

These signals suggest swimming might be aggravating rather than alleviating your condition—a possibility current research can’t adequately predict due to poor study design.

The Critical Three-Week Evaluation

Give swimming a fair trial but establish clear evaluation points:

– Week 1: Focus on technique without pain expectations

– Week 2: Note subtle changes in morning stiffness

– Week 3: Assess functional improvements (bending, lifting)

If you haven’t noticed at least 20% improvement in functional ability by week three, swimming likely isn’t the optimal exercise for your specific back pain pattern. The evidence simply doesn’t support continuing ineffective aquatic therapy when better options may exist.

Bottom Line: While swimming might help your back pain, current research cannot guarantee effectiveness for your specific condition. The lack of quality studies means you’re conducting a personal experiment—not following evidence-based treatment. Track your results meticulously, remain open to land-based alternatives like walking or yoga, and work with your healthcare provider to develop a comprehensive pain management plan that doesn’t rely solely on unproven aquatic therapy. Before committing to months of pool sessions, recognize that the science behind “swimming for back pain” remains more theoretical than proven—a crucial distinction for your recovery journey.